Introduction

There is a great deal of misconception about the role of women in the Middle Ages, misconception that is often carried into “historical’ novels, movies, and games. Although it is true that in most cases women had a very subservient role in society, it’s also true that most men were in a highly subservient position too. The vast majority of the European population, both male and female, were serfs i.e. little better than slaves to the aristocracy. However just as some men managed to elevate themselves from the common herd through heroism, so too did many women. So it is quite fitting with the historical background of the Hidden Tradition to have women adventurers. Here are a few examples…

Clerics, Paladins, & Druids

In most Gnostic sects (and certainly among the Cathars of Montsegur) women had exactly the same clerical status as men. There were Priestesses as well as Priests, and even female Bishops. Female Clerics might wish to identify themselves with this religion.

Pagan religions of all sorts were still fairly popular in Europe by the 12th century, although underground. The worship of Hecate and Asherah in the Hidden Tradition world are examples of this. In many of these religions priestesses were equal to, or superiors of, the male devotees, so this is an excellent background choice for female Druid characters.

Even fairly orthodox mainstream religions had sects that would be considered “out there” by today’s standards. The worship of the Shekinah (female principal) was very popular in Judaism, as of course the worship of the Virgin Mary in Christianity. Here’s a quote:

“A different tradition of female sanctity was also developing in western Christendom over the course of the central and high middle ages, that is the traditions of the ancient female martyrs and saintly penitents. Largely traveling from the Christian east, these began to mature in Latin hagiography in the ninth century, beginning a process of development which would continue for the rest of the middle ages. Simultaneously cults focused on the relics of such women as Mary Magdalene and Catherine of Alexandria (some also imported from the east) grew. By the thirteenth century the legends of these early Christian women were widely disseminated and incorporated into hagiographic collections intended for preachers. The most important of these was the Golden Legend, completed by the Dominican James of Voragine in 1258. Thirty-one of the 182 legends included in this collection concerned female saints, all of them figures from the New Testament or the early church.”

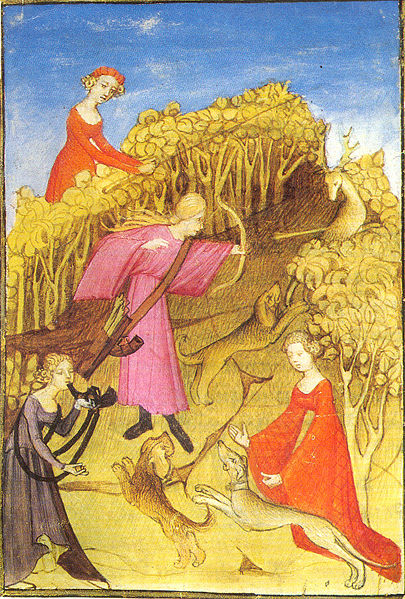

Fighters & Rangers

In the middle ages in Europe, women would fight in time of emergency. Noblewomen were expected to organise and lead the defence of their own home and to lead their troops in the field if they had no male commander whom they could trust with the job (e.g. if they were a widow).

In the middle ages in Europe, women would fight in time of emergency. Noblewomen were expected to organise and lead the defence of their own home and to lead their troops in the field if they had no male commander whom they could trust with the job (e.g. if they were a widow).

Raids on property were common throughout this period. Women were often called upon to defend their homes or castles. The words of Lady Alice Knyvet when faced with troops posed to take her castle probably reflect the motivations and actions of many who were forced into this militant role:

“I will not leave possession of this castle to die therefore; and if you begin to break the peace or make war to get the place of me, I shall defend me. For rather I in such wise to die than to be slain when my husband cometh home, for he charged me to keep it.”

It is not clear how far women fought in the field. Two Muslim sources tell us that women were found dead on the battlefield after a battle outside Acre on 25 July 1190. This account is so vivid that it appears to be true. Western sources say that only ‘common people’ fought that day, so these would have been ordinary women, fighting with the infantry. These sources say that the common people had gone out deliberately without their aristocratic commanders to attack the Muslims themselves because they had lost faith in the nobility to lead them effectively. In this case it is possible that some of the ordinary women (wives, sisters, daughters, mothers) went with the men as part of the common cause. The Muslims were profoundly shocked that the Christian women were fighting, as Muslim women did not fight except in very extreme circumstances, in defence of the home. Some Muslim chroniclers claimed that women were also fighting on horseback in the Christian ranks, as knights, and were identified as women when they were killed and their armour was removed.

At the Battle of Damascus the wife of one of the Arab archers who was killed in battle picked up his bow and immediately joined the conflict. She hit the Crusaders’ standardbearer with one arrow and the commander with another, damaging morale and contributing to the Arab victory.

In the Far East, women samurai were not uncommon, and it was during this period that the famous female warrior Tomoe Gozen fought.

Tomoe had long black hair and a fair complexion, and her face was very lovely, moreover she was a fearless rider whom neither the fiercest horse nor the roughest ground could dismay, and so dexterously did she handle sword and bow that she was a match for a thousand warriors.

In 1184, she led 300 samurai into a fierce battle against 2,000 opposing Tiara clan warriors, and during the Battle of Awazu later that same year, she slayed several adversaries before decapitating the Musashi clan’s leader and presenting his head to her master, General Kiso Yoshinaka.

Bards

Female poets flourished in Southern France between the years 1150-1250. Bogin states that the 400 or so troubadours were not wandering minstrels but serious court poets. The women in their rank were often related to the male poets, served also as patronesses, or both.

And of course there’s the amazing Eleanor of Aquitaine, one of the founders of the whole bardic movement.

Eleanor of Aquitaine was one of the most powerful and fascinating personalities of feudal Europe. At age 15 she married Louis VII, King of France, bringing into the union her vast possessions from the River Loire to the Pyrenees. Only a few years later, at age 19, she knelt in the cathedral of Vézelay before the celebrated Abbé Bernard of Clairvaux offering him thousands of her vassals for the Second Crusade. It was said that Queen Eleanor appeared at Vézelay dressed like an Amazon galloping through the crowds on a white horse, urging them to join the crusades.

While the church may have been pleased to receive her thousand fighting vassals, they were less happy when they learned that Eleanor, attended by 300 of her ladies, also planned to go to help “tend the wounded”.

The presence of Eleanor, her ladies and wagons of female servants, was criticized by commentators throughout her adventure. Although they dressed in armor and carryied lances, the women never fought; although it would seem likely that they fully intended to.